IT IS INTRIGUING to compare how various gardeners deal with the unpleasant reality that when you try to grow challenging plants, or plants novel to horticulture, you inevitably end up with the tags of dead plants. Some gardeners brazenly display them in wide cup fulls, like gruesome trophies. Others discard and hide them like a dirty secret. I have heard plant tags referred to in many ways. Perhaps the most distressing was when a new acquaintance (Bob Heapes, who went on to become a fine rock gardener, president of our chapter, and a dear friend) declared, in disgust, on his first visit to the Rock Alpine Garden that “it looked like the Arlington cemetery of mice.” Admittedly, we had planted a lot of little plants and dutifully retained their glaring white labels until proper plaques could be engraved, but referring to them as “mouse tombstones” went too far. I spent the better part of a week cramming the nasty white things as deep into the ground as I could, breaking a goodly number of them in the process. Thinking back forty years, I suspect most of them truly have turned into plant tombstones.

I’m with the fastidious gardeners who like to trash them immediately. The number of the dear departed can be daunting. I make the mistake of entering all new plant acquisitions in an Excel file, with truly depressing factoids like what the plant cost. That file is 996kb in size (pretty big for Excel) and when I scan it I’m amazed that I could have possibly grown so many plants once upon a time. Worse yet, my photo files are full of phantom plants, some of which I grew for decades. Geoffrey Charlesworth once said, “It doesn’t matter if you’ve grown a plant, it only matters if you photographed it to prove you grew it.” But oh, if one could have that plant back again!

As I was scanning my image files to prepare a talk recently, I kept noticing plants I grew — often in quantity and well — that are now just a memory. I started to take down names thinking some may reappear on the NARGS seedlist, when it occurred to me that each of these seemed to have a story associated with them that could be of interest to fellow rock gardeners. Of course, if you’ve never lost a plant (or if every seed pot you sow germinates promptly and in quantity) there is nothing here of value to read. Go on to the next article, please.

Aethionema capitatum

The so-called “Persian candytufts” occur with special variety and beauty in both Turkey and Greece, many with flowers much deeper rose pink and more compact in habit than Aethionema grandiflorum or A. pulchellum, the most frequently encountered species in rock gardens. A spate of species have been introduced to cultivation in recent decades, many from Turkey which is perhaps the epicenter of the genus and home to its most extreme expressions. I have grown a dozen or more, many of which are wonderful performers, sourced from the Jim and Jenny Archibald or various Czech collectors. The photograph of this species was not taken in my garden (where it never quite attained that size or magnificence) but in the garden of Bill Adams of Sunscapes Nursery in Pueblo, Colorado. Bill’s specimen persisted for many years and provided us all with seedlings that never did quite as well as they did for him (which spurred us on to try harder). This species is basically Aethionema grandiflorum only half the size and more dome-shaped. In other words, perfect. Aethionema grandiflorum spreads widely and grows in almost any condition short of full shade or bog, but its cousin never quite took off the same. Bill sold dozens, if not hundreds, of this over the decades. Surely someone had it thrive for them. Lesson: when a plant is available at a reasonable price and it’s a winner, buy more than one or two and plant them in the likeliest places where they’ll thrive and stay around.

Ajuga chamaepitys var. glareosum

Visitors to my garden are sometimes shocked by the profligacy of the typical form of this species (Ajuga chamaepitys subsp. chia) which can be found in all cardinal points and corners of my yard, though it’s so easy to remove and can be gotten rid of if you work at it. It even thrives with cacti in unwatered beds. Why is its woollier cousin so stubborn by contrast? At one point, I had a dozen or so popping up here and there in a scree, but one by one they disappeared, and one day var. glareosa was gone. Variety chia is beautiful in its own way but var. glareosa’s ermine cape (and more temperamental performance) makes it so much more desirable, especially because we already have the weedier one. Lesson: spend more time eliminating the weedy cousin and less time admiring the pretty one.

Alkanna aucheriana

I grew this from seed from the Archibalds. Jim introduced many extraordinary plants, but usually maintained a suitable Scottish caution in not building expectations too high. This was one he was less restrained about than usual. I recall the price was relatively dear, and my hopes were stratospheric. The silvery foliage, perfect tufted habit, and those flowers did not disappoint. Only it didn’t seem to set seed for us (don’t all bees love blue?) and the plant did not live forever. The one pictured was growing outdoors in a trough in Mike Kintgen’s Denver, Colorado, garden, inspiring a great deal of nostalgic envy for several years. Lesson: try and pollinate your choice plants to encourage them to set seed.

Allium douglasii

As all rock gardeners quickly learn, certain genera are prone to extremes. Viola and Allium can be incredibly pestiferous weeds you have a devil of a time exorcising from your garden or they can be a challenge. A few plants in both genera hug the happy middle and Allium douglasii is one of those. Many of our native onions are attractive and some are even quite showy but few make as big an impact as this endemic of the interior Pacific Northwest with its two-inch (5 cm) spherical blooms of bright purple in high spring. Year after year, it gradually expanded and I wondered: should I divide it in the spring or wait till it goes dormant in the fall? I put it off, the clump got bigger, until one spring it wasn’t there. Rot? Theft? Was it overgrown and I didn’t notice? Lesson: propagate and share. Propagate and share. Don’t be complacent.

Amsonia tharpii

Everyone knows the bluestars, which are mainstays of perennial borders and meadows. They are as valuable for their lemon-yellow fall color as they are for their powder blue puffs of late spring flowers. But what to make of a little cluster of tinier species from the Southwest, which make little vases of silvery foliage with waxy white flowers for weeks in late spring? If they were only orange, or blue like their cousins, or maybe pink, there would be a great demand for these as they are so graceful. I tried growing this species two or three times (the picture was taken at Bill Adams’ garden again) but in retrospect, I realize I probably cooked or dried it out thinking that, since it was Southwestern, it liked to bake. I learned this in time to grow its look-alike cousin Amsonia peeblesii so all isn’t lost: Lesson: because a plant comes from Arizona doesn’t mean it’s a saguaro!

Anagallis monelli ‘Orange Form’

If you garden long enough, you will discover Anagallis monelli (syn. Lysimachia monelli), a stunning mound-forming perennial with cobalt blue flowers with an almost iridescent glow about them. I should say, it’s perennial in Zone 7 or perhaps Zone 8, it’s an annual for us mortals in the colder zones, but still often sold by the more upscale garden centers or nurseries. The species is quite widespread and variable in the Mediterranean basin, and a compact orange form was collected by Mike Kintgen and Rod Haenni that survived several winters in quite a few gardens in the Denver area. I don’t think there are many rock plants that produce such a dazzling and long display of colors. It came readily from cuttings and I remember one spring when hundreds were sold at Denver Botanic Gardens’ spring plant sale. Lesson: when you have a dazzling cultivar, do what you can to keep it.

Androsace sericea

There is no end of white, compact androsaces, all of which are desirable. Not all of them are easy, however. While not as vigorous as Androsace taurica, A. villosa, or a few others in the complex, A. sericea grew well enough for me. I think it came from seed I’d collected off huge mounds of the species studded with tiny seed heads at the base of Nanga Parbat (the ninth highest peak on the planet, and one of the most stunning) in the western Himalayas. I remember seed setting on my plants, which I shared with the exchanges. Lesson: share by all means, but be sure to sow some yourself, too.

Angelica archangelica

Just what a rock gardener needs: a gigantic biennial umbel that towers over the garden and dies after producing a bushel of seed. This is not a rare plant, nor is it particularly choice, but when you look at the picture you can see that it shatters stereotypes. This plant makes green look sexy. It set a ton of seed (which I sowed) and died. The next spring I planted a few here and there where they sputtered and eventually produced a low umbrella or two of “meh” flower clusters. Lesson learned: it’s not the plant in and of itself, it’s how well you grow it. And, as Geoffrey would point out, if you remember to take a picture.

Artemisia tripartita subsp. rupicola

There are plants you love that others cannot fathom. My garden is full of Artemisia, which a Freudian might claim has to do with that being my mother’s first name. No doubt, since I was a “mommy’s boy,” there may be some truth in that, but anyone born and bred in the West had better learn to love the genus. Once you’re smitten, you’d be surprised how many tiny, gnarly, impossibly cute sagebrushes there are. Once you’ve grown a few, you want to grow more. Perhaps 100 miles north of Denver, in Albany County, Wyoming I have seen whole hillsides near Medicine Bow covered with thousands of this gem of a tiny sagebrush interspersed with blazing Indian paintbrush, tiny penstemons, and huge clumps of Cryptantha caespitosa. I managed to capture a little of this magic in a trough where you could enjoy the bonsai-like elegance of the sagebrush up close, with little steppe flowers dancing around it. I enjoyed it for years and years, neglecting to collect seed or taking cuttings. It’s been gone for a decade or more now, and as the growing season closes every year I think I should have driven up to Medicine Bow and collected a few pinches of seed. Maybe next year. Lesson learned: don’t just collect seed, grow it.

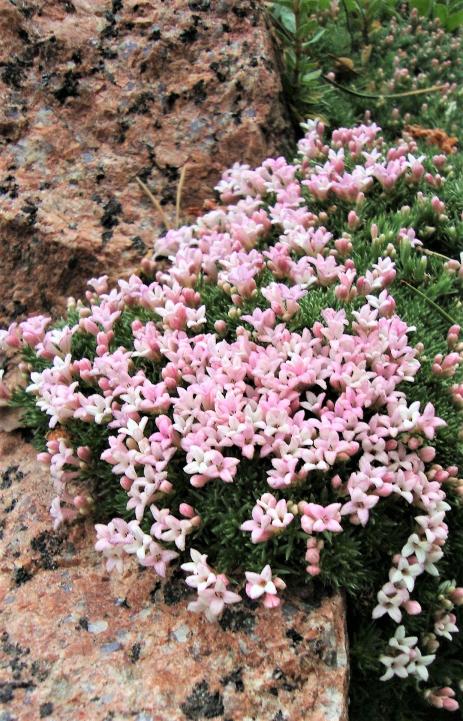

Asperula daphneola

The tiny cousins of woodruff need a good common name. They aren’t really “ruff” and they don’t grow in the woods like their cousin Galium odoratum. There are a dozen or more cushion-forming asperulas that grow at altitude all over the Mediterranean, each one more adorable than the next. Best of all, they seem to persist with a little attention and they’re pretty easy to grow from division, or layerings. No excuse to fumble with these. And when you’ve seen bowling ball-like mounds on a mountain top, as I have, you do tend to watch after them. Except my clump of A. daphneola, which was planted just a little too close to a very vigorous Sempervivum of the arachnoideum persuasion. The two are hopelessly intertwined and I will have to do major surgery (and propagation) to restore the fantastic little mounds of bright pink trumpet blooms that it produced year after year. I promise I shall do so this spring for sure. Lesson learned: make propagation a priority you will honor!

Try as we may, we will inevitably lose plants, often those that we took special pride in and which reigned supreme in our gardens. Consider that in this article I only dipped into the first letter of the alphabet. There is a phantom rock garden in my slide files filled with wonderful gems I still yearn for. At least I can enjoy their images.